What Is Dynamic DNS (DDNS)?

Dynamic DNS is a service that automatically updates a domain name's DNS record when its associated IP address changes.

It allows devices with frequently changing IP addresses to remain reachable through a consistent domain name. This is commonly used when internet service providers assign dynamic IPs instead of static ones.

While traditional DNS is widely used across all internet-connected systems, DDNS is a more niche utility.

It's not generally considered an enterprise-scale solution.

What created the need for DDNS?

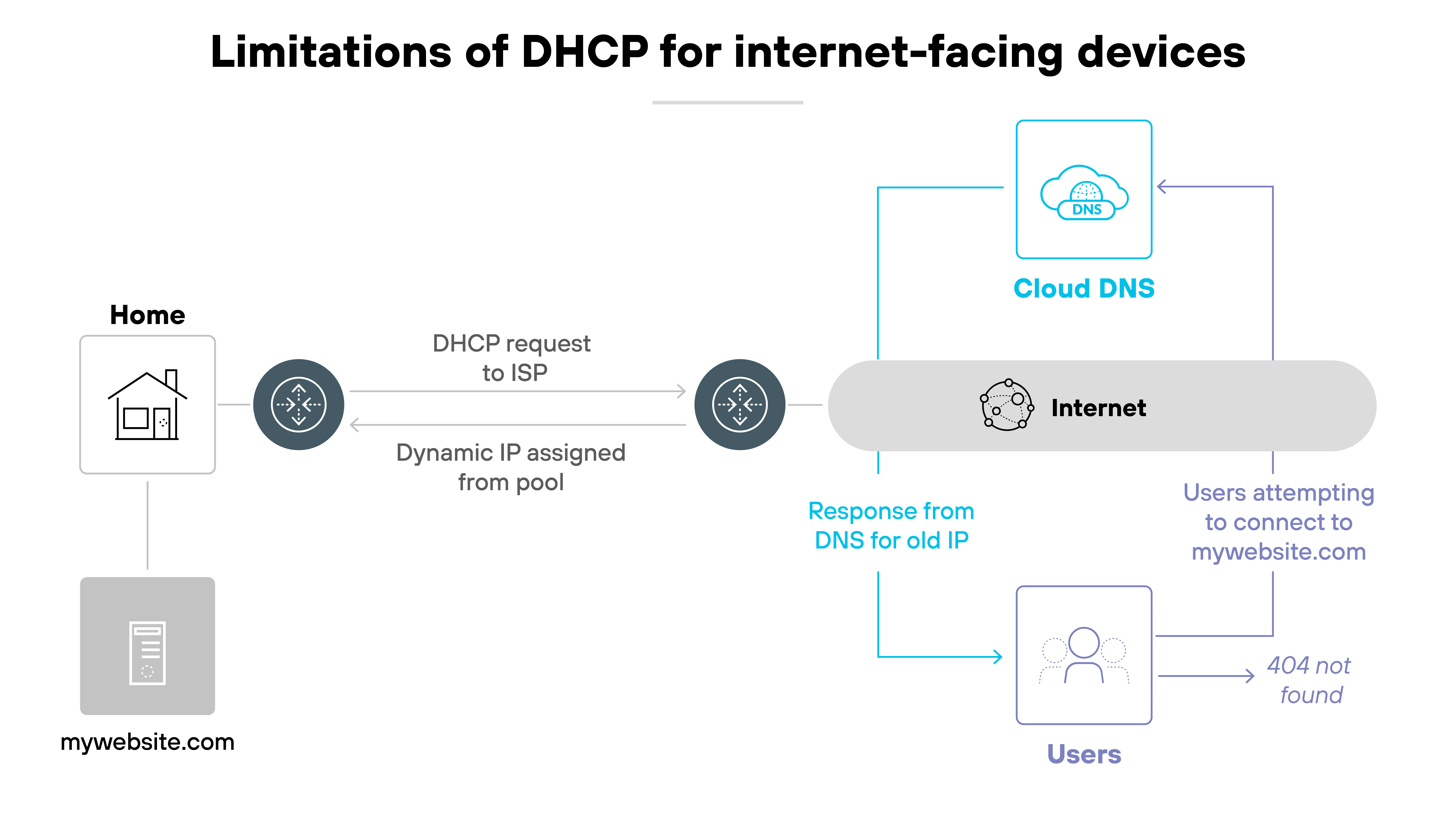

As home and small business internet access became common, internet service providers began assigning dynamic IP addresses—temporary addresses that could change at any time.

This approach helped providers manage limited address space, but it created a challenge for users who needed consistent remote access to their networks.

If your IP address changes without warning, it becomes difficult to connect to devices like personal servers, smart home systems, or remote desktop setups. You might not know the current address. And even if you do, it might change again tomorrow.

That's where dynamic DNS comes in.

It automatically updates the DNS record associated with your domain name whenever your IP address changes. That way, your hostname always points to the correct address, no matter how often your ISP changes it.

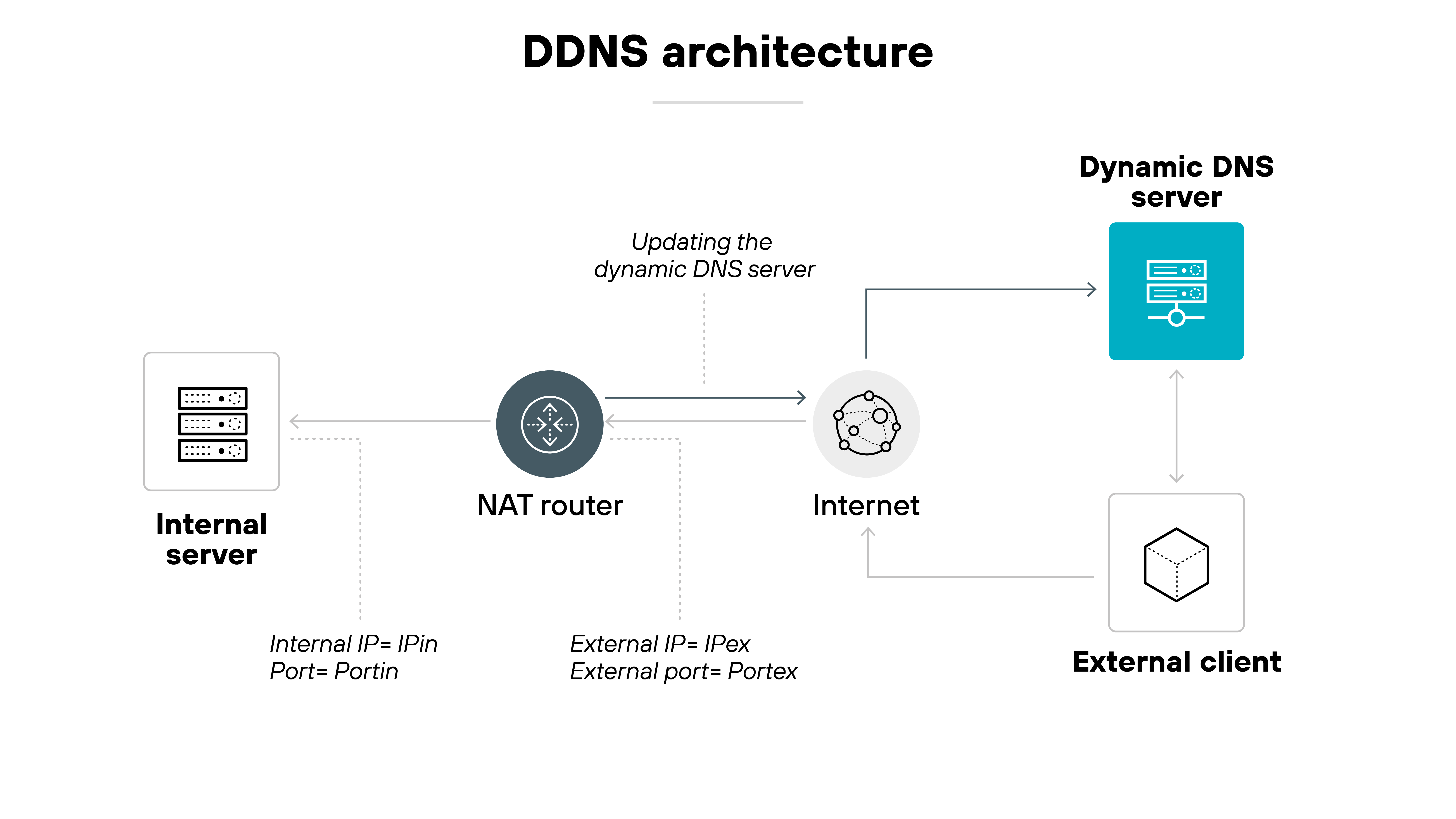

How does DDNS work?

Dynamic DNS starts with a domain name registered through a DDNS provider.

The provider hosts the DNS records and updates them automatically whenever your IP address changes.

A DDNS client—either running on a local device or built into your router—monitors your public IP and triggers those updates when needed.

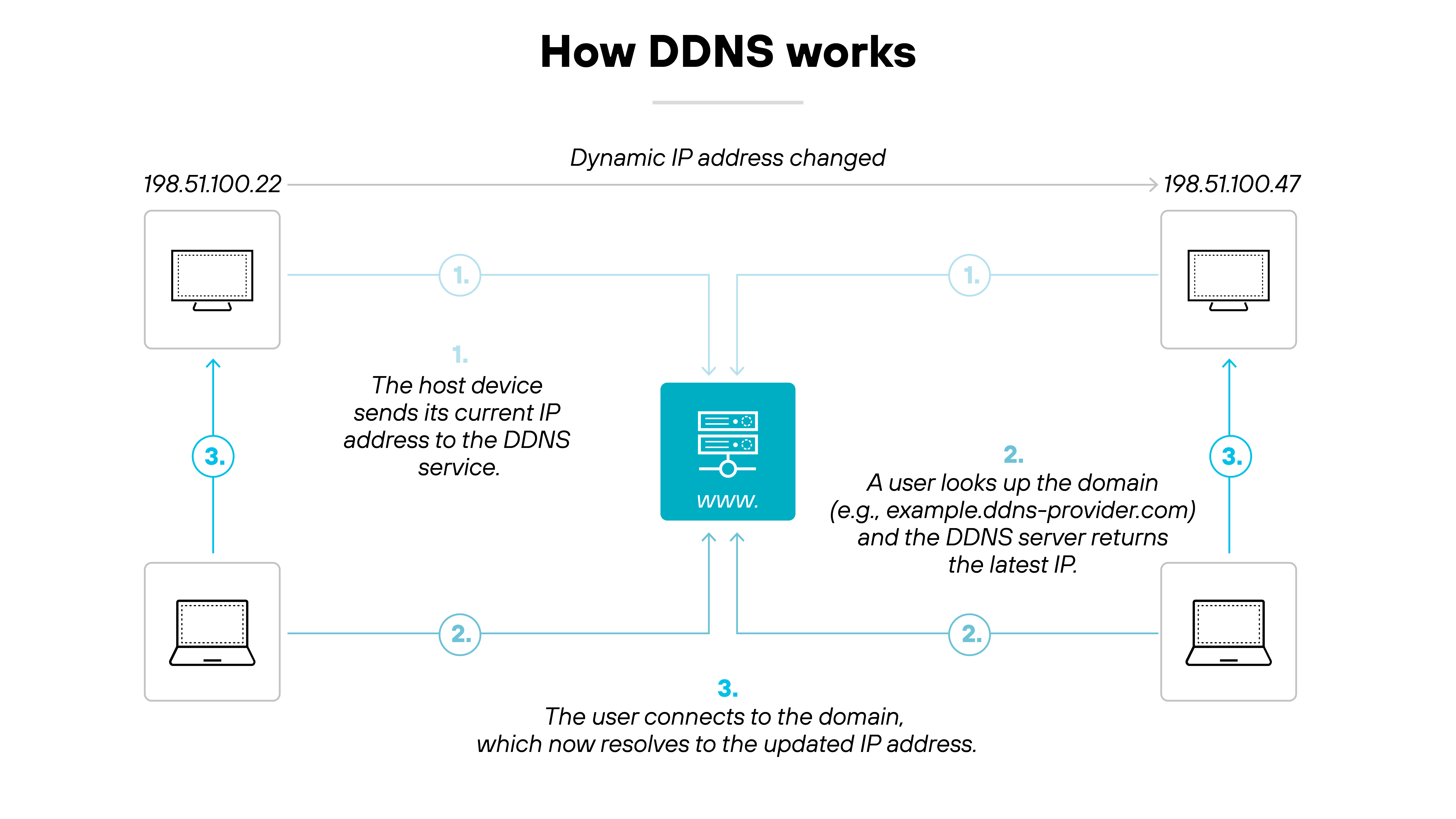

Here's how the process works step by step:

- You register a domain name with a DDNS provider and link it to your current IP address.

- You install a DDNS client that monitors your IP address for changes.

- When the IP address changes, the client notifies the DDNS provider.

- The provider updates the DNS record so the domain always points to the correct IP.

- This process runs continuously to keep the domain in sync.

In networks using NAT, port forwarding is often needed to make internal services reachable from the internet.

DDNS keeps the domain name remains accurate even when the public IP changes. And this allows consistent remote access without manual DNS updates.

It's easy to set up, but typically used in branch offices, labs, demo sites, small-scale business environments, or by technical users hosting services at home.

Basically, DDNS provides a lightweight, cost-effective way to expose services without buying static IPs or deploying a full DNS stack.

What does DDNS help with?

DDNS is designed to solve one specific problem: keeping a domain name pointed to the right place when your IP address changes.

That makes it useful in a handful of specialized scenarios. Here are some common examples:

- Remote access to a home network: Accessing a file server, VPN, or remote desktop setup from outside your home.

- Self-hosted services on a dynamic IP: Running a website, FTP server, or gaming server from your home internet connection.

- Surveillance and smart home monitoring: Connecting to security cameras, DVRs, or smart devices that don't use a cloud service.

- Test environments and sandbox servers: Developers using dynamic cloud instances without load balancers or static IPs.

In all of these cases, the goal is the same: Avoid connection issues by keeping a domain name synced with a changing IP address.

DDNS is mostly used by hobbyists, home lab enthusiasts, and small businesses that want to host services without paying for a static IP.

What are the benefits of DDNS?

There's really just one benefit of DDNS: staying reachable when your IP address changes.

That's the core purpose—and everything else stems from it.

DDNS lets you keep a domain name synced to a changing IP, which means services like home servers, remote desktops, or smart devices remain accessible without needing to manually update DNS records every time your IP shifts.

Other “benefits” are really just side effects of this one function:

- You don't have to pay for a static IP — but that's only helpful if you're okay with the trade-offs that come with dynamic addressing. In most business environments, you'd pay for stability instead.

- It requires less manual maintenance, but that only applies if you're already managing your own DNS or hosting services at home. For most people, these aren't things they're doing in the first place.

- It works for small-scale setups, but DDNS is rarely used in modern enterprises or cloud-native architectures. If scale is your concern, there are better options.

DDNS is a practical tool for very specific situations. Again, usually hobbyist or budget-constrained business setups. But it's not a broadly applicable networking solution. Its simplicity is its strength, but also its limitation.

What are the different types of DDNS implementations?

| Type of DDNS | How it works | Good for |

|---|---|---|

| Client-based | A lightweight app runs on a local device and updates the DNS record when the public IP changes. | Users hosting a server or camera from an always-on PC or NAS. |

| Router-based | The router detects IP changes and sends updates directly to the DDNS provider. | Anyone who wants a simple, always-running solution with no extra device. |

| Custom/API-based | A script or tool calls the DNS provider's API to update records when the IP changes. | Users comfortable with scripting or programmable DNS tools. |

| Enterprise-style | You sign up with a provider that offers plug-and-play tools (apps, router support, etc.). | Non-technical users who want a quick setup for home or small office use. |

| Turnkey services | Internal name resolution using DHCP and DNS servers—does not update public DNS. | Enterprises managing internal hostnames—not for internet-facing services. |

There are a few different ways to use DDNS, depending on your setup and technical skill level.

Each method ultimately does the same thing—keep a domain name synced with your current IP—but the approach varies by device, tooling, and user preference.

Client-based (software installed on a PC or NAS)

This setup uses a lightweight app installed on a local machine. It monitors your public IP address and updates the DDNS provider whenever it changes.

Good for: Users running a home server, NAS, or camera from an always-on computer.

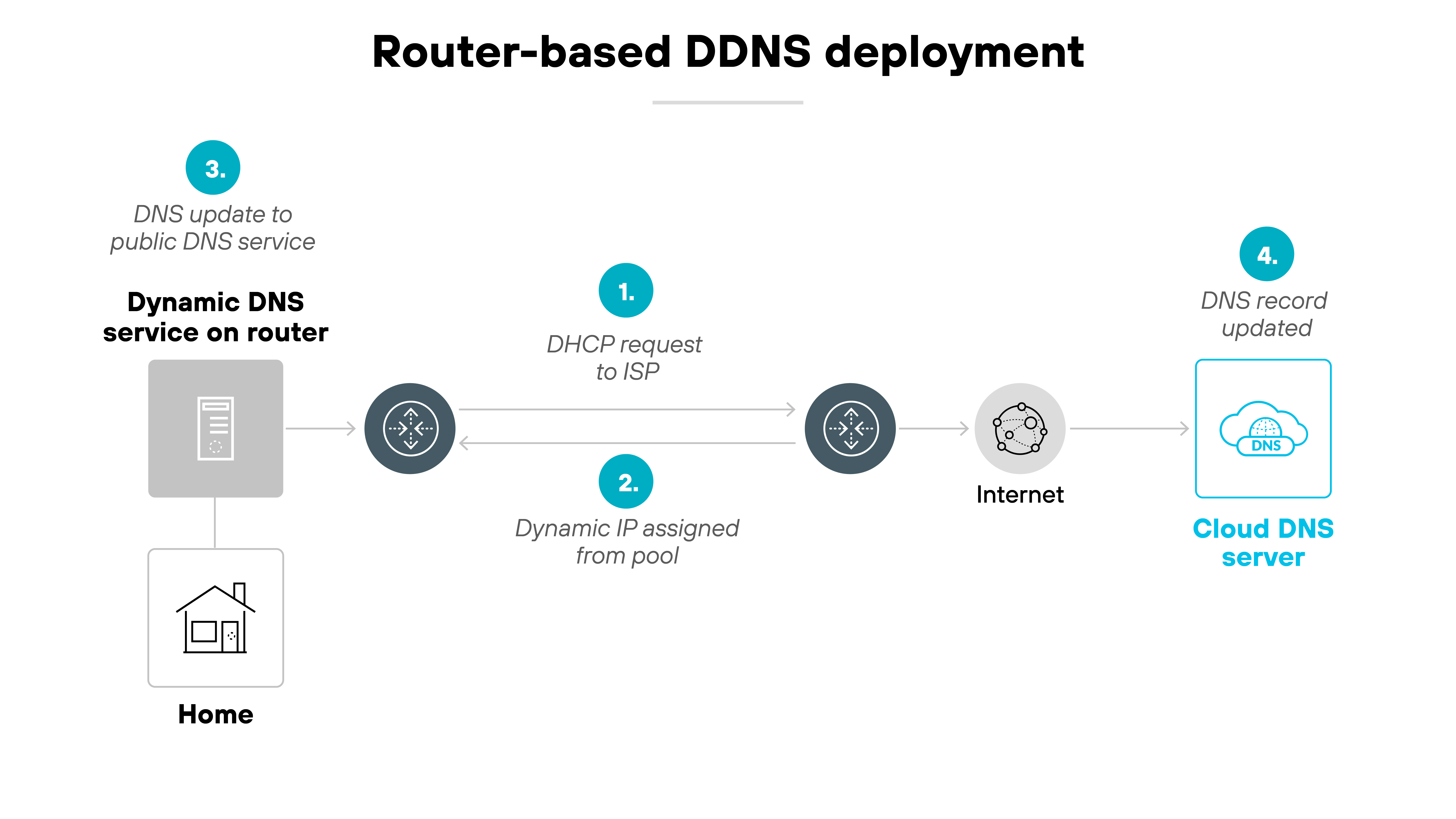

Router-based (DDNS built into your router)

Some routers include DDNS support directly. When the router detects a new IP from the ISP, it sends an update to your DDNS provider—no other device or app required.

Good for: Users who want a simple, always-on setup that doesn't depend on a specific computer.

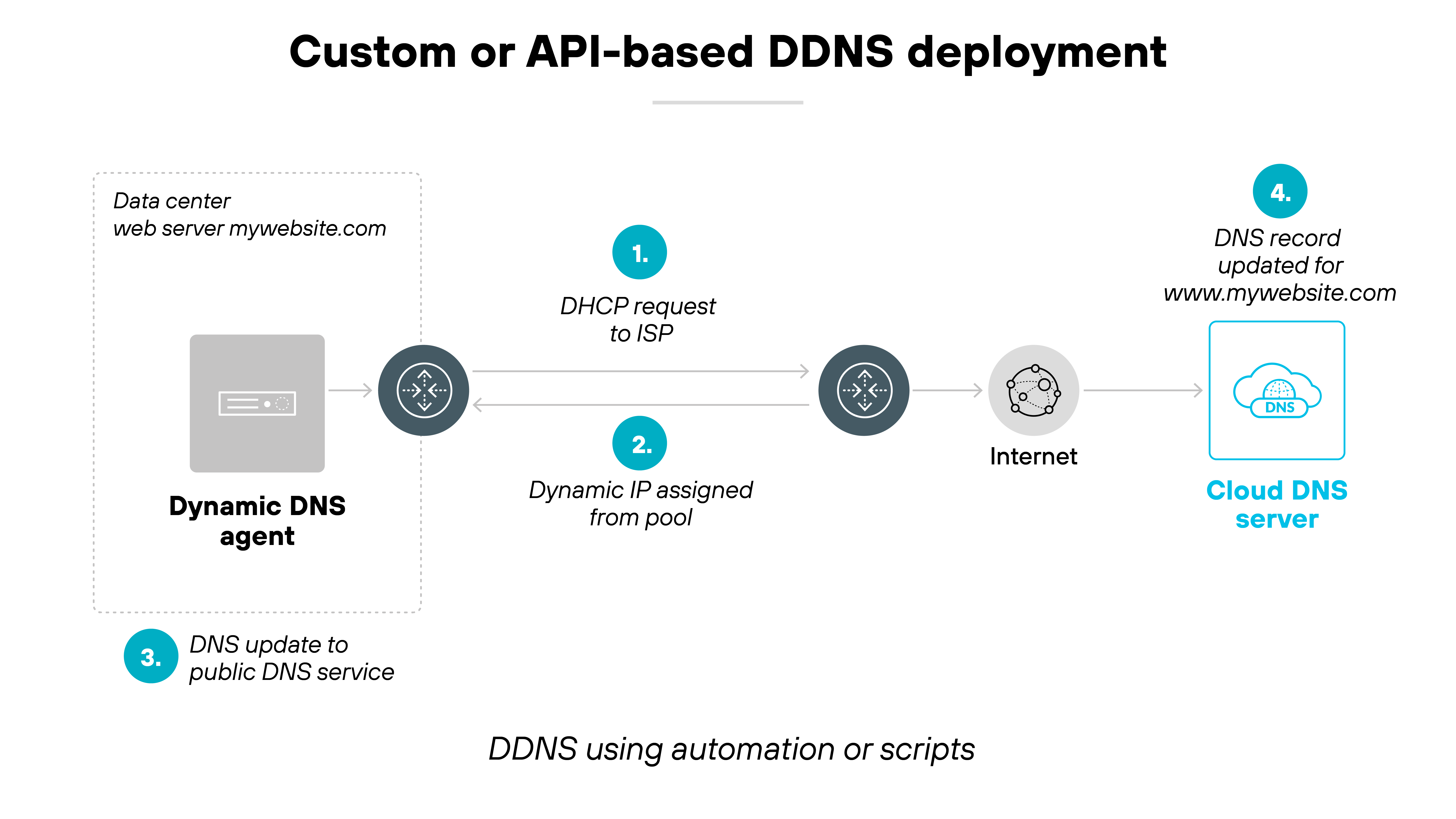

Custom or API-based (scripts and automation tools)

This method involves writing a custom script or using a third-party tool to update DNS records through an API. The script typically runs on a local machine or server and communicates directly with DNS providers that support dynamic updates. It's flexible, but requires some technical skill to set up.

Good for: Tech-savvy users who want control or already use programmable DNS services.

Turnkey services (plug-and-play DDNS from a provider)

These are all-in-one solutions where the provider gives you everything you need—apps, router integrations, or setup guides—to keep your domain synced.

Good for: Users who want an easy, provider-managed option with minimal setup.

- The functionality is the same across all methods. The difference is how much of the setup is manual versus pre-packaged.

- Enterprise networks typically use internal DHCP and DNS servers to manage device names within the network. These systems may automatically update internal records, but they don't update public DNS. That's internal name resolution, not dynamic DNS.

What are the security risks of DDNS?

DDNS isn't inherently dangerous. But in business networks, its presence can be a red flag.

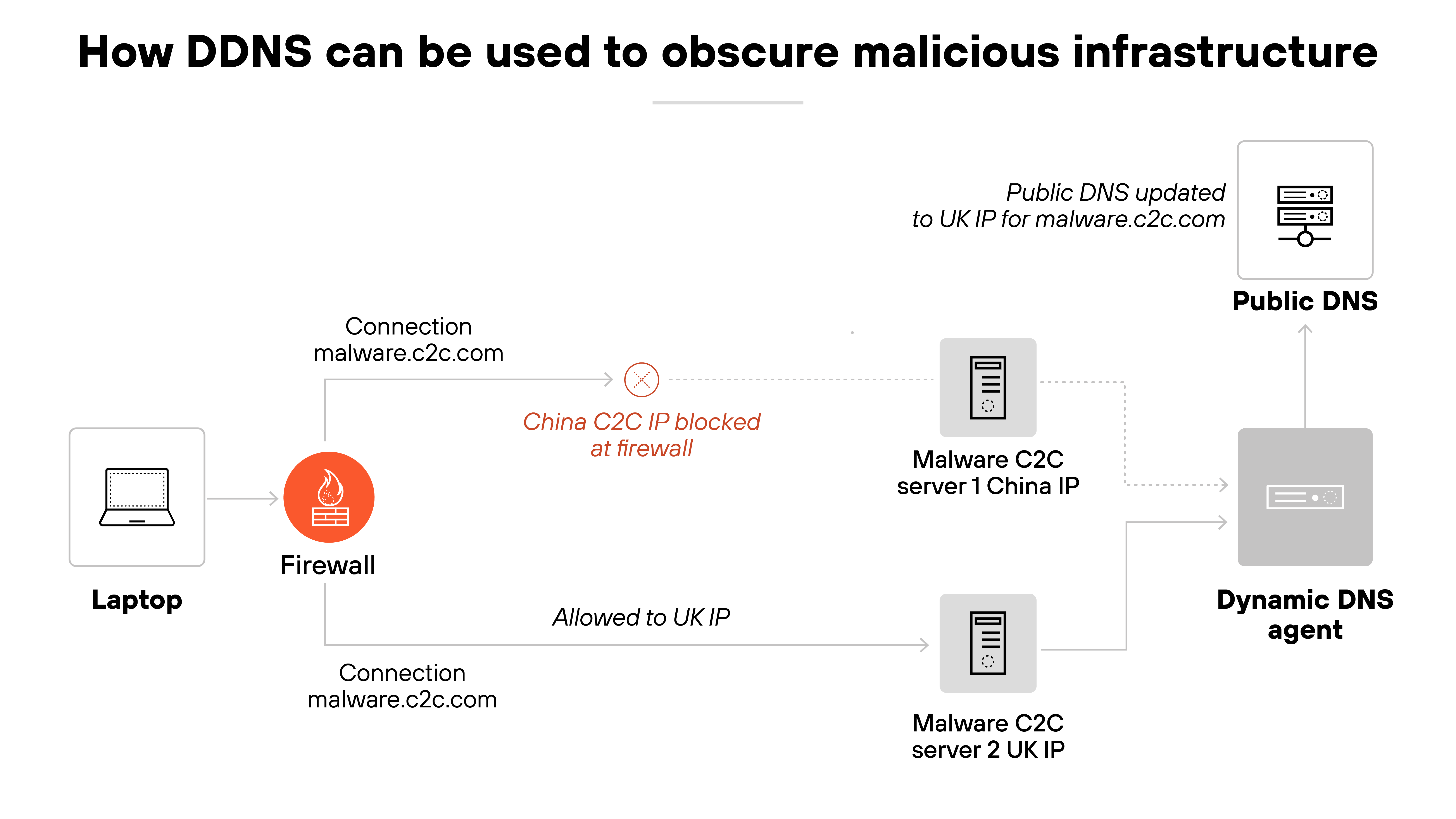

Because DDNS allows domains to point to changing IP addresses, attackers often use it to support malicious infrastructure that needs to stay flexible and hard to track.

Malware, for example, may use a DDNS-registered domain to communicate with a command-and-control server. If defenders block the server's current IP, the attacker can simply update the DNS record with a new one—keeping the malware online.

Like this:

That's why DDNS is often flagged in threat intelligence tools. Because it shows up in phishing campaigns, payload delivery systems, and persistent malware callbacks.

So while not malicious on its own, DDNS is commonly abused in real attacks.

The bigger issue?

In enterprise environments, there are very few legitimate reasons to use DDNS.

Most organizations use static IPs, VPNs, or private overlays—so DDNS traffic tends to stand out. Security teams often treat outbound connections to DDNS domains as suspicious until proven otherwise.

Bottom line:

If DDNS shows up in network traffic, it doesn't always mean there's a problem. But it usually warrants investigation. That's less about the technology itself and more about how rarely it's used for legitimate purposes in business settings.

What is the difference between DNS and DDNS?

DNS and DDNS aren't different technologies—they use the same system.

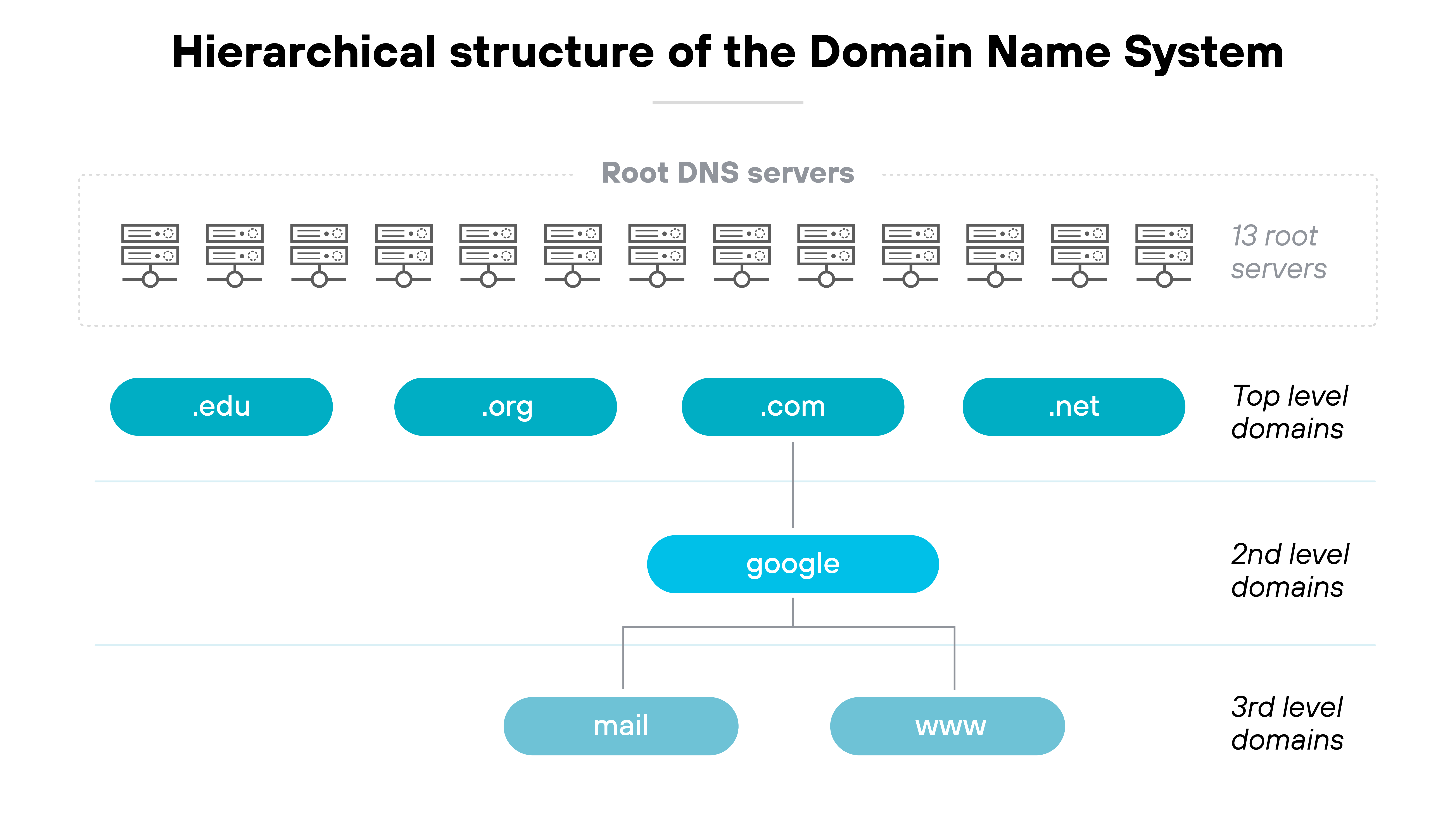

DNS (Domain Name System) is the foundational service that maps domain names to IP addresses.

DDNS, or Dynamic DNS, is simply a way of automating DNS updates when an IP address changes. It doesn't replace DNS or work differently—it just removes the need for manual updates.

Static DNS vs. DDNS

| Feature | DNS | DDNS |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Manually maps domain names to IP addresses | Automates updates to DNS records when IPs change |

| IP address handling | Assumes IPs stay the same | Handles frequent IP address changes |

| Update mechanism | Manual updates by admins or scripts | Automatic updates via client or router |

| Use case | Hosting websites, business infrastructure with static IPs | Home labs, remote access, dynamic or consumer networks |

| Reliability with dynamic IPs | Low — breaks if IP changes and record isn't updated | High — auto-updates maintain access |

| Configuration requirement | Basic DNS setup | Requires DDNS client or router support |

| Provider dependency | Can be self-hosted or use any DNS provider | Depends on a specific DDNS provider |

| Network type suitability | Stable, static environments | Dynamic, typically consumer-grade environments |

More specifically:

DNS, or Domain Name System, is the standard system used to translate domain names into IP addresses. When someone enters a domain like example.com, DNS resolves that name to the correct IP address so the browser can reach the right server. This system is globally distributed and doesn't change unless a user or administrator updates the DNS record manually.

DDNS, or Dynamic DNS, builds on this concept by automating updates to DNS records when an IP address changes. This is especially useful in networks where public IP addresses are assigned dynamically by the internet service provider. With DDNS, the domain name remains accurate without requiring constant manual adjustments.

Dynamic DNS (DDNS) doesn't change how DNS works—it just automates the part where someone would otherwise have to manually update a record. That automation is helpful in setups where the public IP address can change without warning, like home networks or test environments that don't use static IPs.